#anna komnenos

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The thing that gets me about Roman Empire being (arguably) the longest lived state in history is how much they had shifted in culture and language, and yet remained Roman. The founders of the Roman State would have surely considered the late-medieval empire an abomination. Anna Komnenos uses the word 'Latin' to describe the Normans her father fought against. They've lived so long that a word that described their founders has become an almost pejorative term for their enemies! The East-West schism of Christianity happened partially because of the language barrier, the Roman Church spoke Latin and the Roman Empire didn't, it spoke Greek! But they're still Roman. Alexius Komnenos was just as much a Roman emperor as Caesar Augustus.

#roman empire#anna komnenos#alexios komnenos#ship of thesus ass empire#everything has changed but they're the same#new capital new language new culture but it's still rome#some things never change though#anna still calls all western europeans celts#even the normans who definitely are not celts#absolutely no time for whatever bullshit is going on in western europe unless it helps them recruit into the varangians

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 21: Anna Dalassene, mother of Alexios I Komnenos. Anna took charge of managing her family’s future upon the death of her husband, orchestrating marriage alliances and advocating for her sons to attain positions of command in the military. She was instrumental in Alexios’s rise to the throne and administered from Constantinople while he was away on campaign.

#grayjoytober2024#anna dalassene#historical women#history art#traditional art#byzantium#byzantine empire#byzantine empress#constantinople#medieval#greek tag#roman tag#11th century#inktober#inktober 2024#drawtober#drawtober 2024

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wives and Daughters of Byzantine Emperors: Ages at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list.

Theodora, wife of Justinian I; age 35 when she married Justinian in 435 AD

Constantina, wife of Maurice; age 22 when she married Maurice in 582 AD

Eudokia, wife of Heraclius; age 30 when she married Heraclius in 610 AD

Fausta, wife of Constans II; age 12 when she married Constans in 642 AD

Maria of Amnia, wife of Constantine VI; age 18 when she married Constantine in 788 AD

Theodote, wife of Constantine VI; age 15 when she married Constantine in 795 AD

Euphrosyne, wife of Michael II; age 33 when she married Michael in 823 AD

Theodora, wife of Theophilos; age 15 when she married Theophilos in 830 AD

Eudokia Dekapolitissa, wife of Michael III; age 15 when she married Michael in 855 AD

Eudokia Ingerina, wife of Basil I; age 25 when she married Basil in 865 CE

Theophano Martinakia, wife of Leo VI; age 16/17 when she married Leo in 882/883 AD

Helena Lekapene, wife of Constantine VII; age 9 when she married Constantine in 919 AD

Theodora, wife of John I Tzimiskes; age 25 when she married John in 971 AD

Theophano, wife of Romanos II (and later Nikephoros II); age 14 when she married Romanos in 955 AD

Anna Porphyrogenita, daughter of Romanos II; age 27 when she married Vladimir in 990 AD

Zoe Porphyrogenita, wife of Romanos III (and later Michael IV & Constantine IX); age 50 when she married Romanos in 1028 AD

Eudokia Makrembolitissa, wife of Constantine X Doukas (and later Romanos IV Diogenes); age 19 when she married Constantine in 1049 AD

Maria of Alania, wife of Michael II Doukas (and later Nikephoros III Botaniates); age 12 when she married Michael in 1065 AD

Irene Doukaina, wife of Alexios I Komnenos; age 11 when she married Alexios in 1078 AD

Anna Komnene, wife of Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger; age 14 when she married Nikephoros in 1097 AD

Maria Komnene, daughter of Alexios I Komnenos; age 14/15 when she married Nikephoros Katakalon in 1099/1100 AD

Eudokia Komnene, daughter of Alexios Komnenos; age 15 when she married Michael Iasites in 1109 AD

Theodora Komnene, daughter of Alexios Komnenos; age 15 when she married Constantine Kourtikes in 1111 AD

Maria of Antioch, wife of Manuel I Komnenos; age 16 when she married Manuel in 1161 AD

Euphrosyne Doukaina Kamatera, wife of Alexios III Angelos; age 14 when she married Alexios in 1169 AD

Maria Komnene, daughter of Manuel I Komnenos; age 27 when she married Renier of Montferrat in 1179 AD

Anna of France, wife of Alexios II Komnenos (and later Andronikos Komnenos); age 9 when she married Alexios in 1180 AD

Eudokia Angelina, daughter of Alexios III Angelos; age 13 when she married Stefan Nemanjic in 1186 AD

Margaret of Hungary, wife of Isaac II Angelos; age 11 when she married Isaac in 1186 AD

Anna Komnene Angelina, daughter of Alexios III Angelos; age 14 when she married Isaac Komnenos Vatatzes in 1190 AD

Irene Angelina, daughter of Isaac II Angelos; age 16 when she married Philip of Swabia in 1197 AD

Philippa of Armenia, wife of Theodore I Laskaris; age 31 when she married Theodore in 1214 AD

Maria of Courtenay, wife of Theodore I Laskaris; age 15 when she married Theodore in 1219 AD

Maria Laskarina, daughter of Theodore I Laskaris; age 12 when she married Bela IV of Hungary in 1218 AD

Elena Asenina of Bulgaria, wife of Theodore II Laskaris; age 11 when she married Theodore in 1235 AD

Anna of Hohenstaufen, wife of John III Doukas Vatatzes; age 14 when she married John in 1244 AD

Theodora Palaiologina, wife of Michael VIII Palaiologos; age 13 when she married Michael in 1253 AD

Anna of Hungary, wife of Andronikos II Palaiologos; age 13 when she married Andronikos in 1273 AD

Eudokia Palaiologina, daughter of Michael VIII Palaiologos; age 17 when she married John II Megas Komnenos in 1282 AD

Irene of Montferrat, wife of Andronikos II Palaiologos; age 10 when she married Andronikos in 1284 AD

Rita of Armenia, wife of Michael IX Palaiologos; age 16 when she married Michael in 1294 AD

Simonis Palaiologos, daughter of Andronikos II Palaiologos; age 5 when she married Stefan Milutin in 1299 AD

Irene of Brunswick, wife of Andronikos III Palaiologos; age 25 when she married Andronikos in 1318 AD

Anna of Savoy, wife of Andronikos III Palaiologos; age 20 when she married Andronikos in 1326 AD

Irene Palaiologina, daughter of Andronikos III Palaiologos; age 20 when she married Basil of Trebizond in 1335 AD

Maria-Irene Palaiologina, daughter of Andronikos III Palaiologos; age 9 when she married Michael Asen IV of Bulgaria in 1336 AD

Theodora Kantakouzene, daughter of John VI Palaiologos; age 16 when she married Orhan Gazi in 1346 AD

Helena Kantakouzene, wife of John V Palaiologos; age 13 when she married John in 1347 AD

Keratsa of Bulgaria, wife of Andronikos IV Palaiologos; age 14 when she married Andronikos in 1362 AD

Helena Dragas, wife of Manuel II Palaiologos; age 20 when she married Manuel in 1392 AD

Anna of Moscow, wife of John VIII Palaiologos; age 21 when she married John in 1414 AD

Maria Komnene, wife of John VIII Palaiologos; age 23 when she married John in 1427 AD

Helena Palaiologina, daughter of Theodore II Palaiologos; age 14 when she married John II of Cyprus in 1442 AD

Helena Palaiologina, daughter of Thomas Palaiologos; age 15 when she married Lazar Brankovic in 1446 AD

Sophia Palaiologina, daughter of Thomas Palaiologos; age 23 when she married Ivan III of Russia in 1472 AD

The average age at first marriage was 17 years old.

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mehmed II Conqueror + consorts (pictures are for aesthetic)

Emine Gülbahar Hatun — was a favourite consort of Sultan Mehmed II. In most sources she is referred as non-muslim slave who was converted to Islam after her arrival to the harem. There is no agreement on her origins some historians think she was Pontic Greek, Albanian or lowly Slavic. She was the mother of the future Sultan Bayezid II and Gevherhan Hatun. She died circa 1492 and was buried in her mausoleum inside the Fatih Mosque next to her late husband.

Çiçek Yagmur Hatun — was a wife or consort of Sultan Mehmed II. According to some sources she could have been Turkish noblewoman or Serbian, Greek, Venetian, French slave. She entered the harem or married Mehmed at Constantinople and gave birth to her only son Şehzade Cem (Ottoman claimant Sultan) on 22 December 1459. It is not known the degree of influence she had during Mehmed’s reign or if she even was favoured by him. She died on 3 May 1498 of plague and was buried in Cairo.

Hatice Hatun — was a thrid legal wife of Sultan Mehmed II. She was a possible daughter of Zaganos Mehmed Pasha. In 1463 she became Mehmed's third legal wife. After her husband death she remarried with a statesman.

Sitti Mükrime Hatun — was a Turkish Princess and first legal wife of Sultan Mehmed II. Her father was Süleyman Bey the sixth ruler of Dulkadir State. When Mehmed turned seventeen he married her for political purposes. Her possible offspring is unknown. Due to her middle name Sittişah is sometimes confused with Gülbahar Mükrime Hatun another consort of Mehmed. She died in September 1486 and was buried in a mausoleum built inside her mosque.

Helena Palaiologina — was a possible wife of Sultan Mehmed II. Her entering the Sultan's harem is controversial and remain unconfirmed. She was a daughter of the Despot of Morea Demetrios Paleologos the brother of Constantine XI Palaiologos the final Byzantine emperor and Theodora Asanina the daughter of Paul Asan. Some rumors says Mehmed II asked for her after his campaign in Morea having heard of her beauty. Probably he never bedded with her because he was afraid she would poison him. In another case Helena was provided with a pension and large estate at Adrianople by the Sultan though she was forbidden to marry. She died of unknown causes in 1469 or 1470 in Edirne.

Gülşah Hatun — was a second legal wife or consort of Sultan Mehmed II. There is no informations about her origins. She married Mehmed or entered his harem in 1449 when he was still a Prince and the governor of Manisa. Shortly before Murad’s II death she gave a birth to her only son Şehzade Mustafa and followed him to Konya when he became governor of the province. She died circa 1487 and was buried in Bursa in the tomb she had built for herself near that of Mustafa.

Maria Hatun — was a consort of Sultan Mehmed II. Before she entered Mehmed’s harem she was a widow of Alexander Komnenos Asen. According to some sources she was judicated as the most beautiful woman of her age. Some historians claims she could be more likely Murad’s II concubine than Mehmed’s.

Anna Hatun — was a consort of Sultan Mehmed II. Her parents were Trabzon Greek emperor David Komnenos and Helena Kantakuzenos. The marriage was initially proposed by her father, but Mehmed refused. Nontheless when Trabzon was taken in 1461 Anna entered the harem and stayed there for two years after which Mehmed married her off to Zaganos Mehmed Pasha.

#ottoman history#mehmed ii#consort#gulbahar hatun#cicek hatun#helena hatun#hatice hatun#maria hatun#sitti hatun#anna hatun#ottoman empire#aestehtic#history#historyedit#sultanate#wives#myedit#ottoman ladies

118 notes

·

View notes

Note

Which Byzantine figures do you consider underrated? As someone who has slowly started to learn more about Byzantium, names like Constantine the Great, Justinian the Great, Theodora, Irene of Athens, Anne Komnene, Nikephoros Phokas, Constantine Palaiologos, Tsimiski, Basil, Zoe and Theodora Porprhyrogennita and Theophano are familiar, but do you have any other recommendations (sorry if I misspelled some)?

Below are a few Byzantine historical figures I find very interesting currently:

Flavius Belisarius (c.500 - 565)

While Justinian the Great is one of the most significant emperors in history, his accomplishments would simply not be the same, if he did not have Belisarius as his military commander. He was of uncertain descent (possibly Thracian, Illyrian or less so Greek) but his mother tongue was certainly Latin. Belisarius reconquered Rome and Italy while severely outnumbered during the Gothic War, defeated the Sassanids in the Iberian War, conquered the Vandal Kingdom in North Africa, successfully repulsed the Huns and defended the empire from the Persians and the Arabs. The Byzantine Empire reached its largest surface mostly thanks to Belisarius. A more controversial point in his life was when he was commanded to suppress the notorious Nika riots against Justinian, which ended in a massacre of dozens of thousands civillians. Belisarius was above all a strategist; he didn't mind fleeing the battle or using trickery in order to win a war. Despite his analytical mind in battle, he resolutely wasn't one in the affairs of the palace. Belisarius was married and quite smitten with Antonina, who had the favour of Empress Theodora, and thus felt safe to be totally unhinged. Schemes happening in the palace would sometimes find a scapegoat in Belisarius, who was likely the most genuinely devoted person to the emperor. As a result, Belisarius was often not treated well by the emperor and the secretaries and he was cheated on by his wife. He was even led to trial for betrayal, although Justinian eventually pardoned him. According to legend, Justinian first blinded him and then pardoned him, although lately the historicity of this is questioned. What's certain is that Belisarius didn't receive the respect he deserved in his personal life but he earned the respect of the historians, who consider him one of the best military leaders in history.

Ioannis II Komnenos (1087 - 1143)

Known as Kaloioannis (John the Good / Beautiful), Ioannis is considered the best emperor from the Greek dynasty of the Komneni. Ioannis was not beautiful, he must have been rather unattractive actually, but he earned the title because of his noble character. He was the brother of Anna Komnene, he was the one she tried to poison so that she would ascend to the throne instead. Ioannis forgave her. Ioannis was very just, modest and pious and would only use his imperial luxuries during diplomat visits. He was married to Irene of Hungary. Whether it was because of his piety, his natural predesposition or a different orientation, Ioannis was not very interested in the joys of marriage. However, he remained devoted and faithful to her. It is notable that during his long reign, not a single person was sentenced to death or mutilation, at a time that this would have been the norm for criminals and traitors. Despite all that, Ioannis was actually a great military leader once need arose. His biggest goal as an emperor was to undo the damage from the Battle of Manzikert 50 years prior. Indeed he forced Seljuk Turks to assume a defensive stance and did expand the empire's power to the east again. The Byzantine population increased during his reign. It is certain that Ioannis left the empire significantly better than how he received it. Some sources suggest that Ioannis' noble character was an inspiration to the people of his empire.

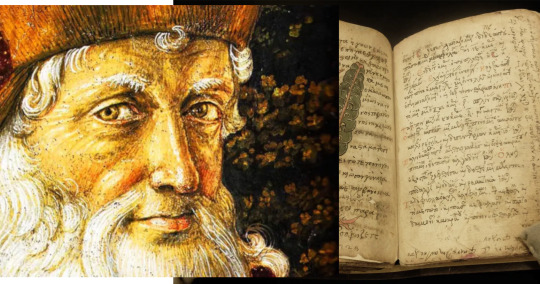

Michael Psellos (1017 - 1078)

Psellos was a Greek man of great knowledge and intellect and a questionable character. He did it all; he was a monk, a writer, a philosopher, a judge, a music theorist, an imperial advisor and courtier and a historian. His skill in literally everything led him quickly to the position of the leading professor in the University of Constantinople and that of secretary in the imperial court. His political influence was immense and he saw many emperors succeed each other while he maintained his position as political advisor. Because a big part of his work is autobiographical, it is unclear whether some of his claims are entirely reliable; Psellos was prone to vanity and sarcasm against those who did not favour him. Psellos studied Plato thoroughly, so much so that at times his faith in Christian Orthodoxy was questioned. *Fun fact: Psellos was apparently good at everything except Latin. His Latin was so rusty he confused Cicero with Caesar!

He looks like a Greek Rasputin in his painting above lol Anyway, he was manipulative but he wasn't nowhere near as controversial as Rasputin, let me be clear.

Georgios Gemistos Plethon (c. 1355 - 1452/1454)

Gemistos Plethon was a scholar and philosopher of the late Byzantine era. He was the pioneer of the revival of Greek scholarship in Western Europe. He was secretly not Christian, he believed in the Ancient Greek gods. Plethon admired Platon too. (It's Platon in Greek.) So much so that he added "Plethon" next to his surname Gemistos, which means pretty much the same thing (full) except more archaic and more similar to Plato(n)'s name! He was imperial advisor to the Palaeologi dynasty who at the time were reigning from Mystras, as the empire was dissolving. Everyone suspected his pagan beliefs but he was so influential and important that nobody dared confront him about it. He taught philosophy, astronomy, history, geography and classical literature. He was invited to Florence, Italy to teach Plato and Aristotle and help Florentines understand the differences between the two philosophies. Plethon died in Mystras shortly before or after the Fall of Constantinople. We don't know if he lived enough to see the empire fall. Around 10 years later, some of his Italian followers stole his remains from Mystras and interred him in Rimini, Northern Italy, so that he could "rest amongst free men". Plethon's vision was the revival of the Byzantine Empire, founded on a utopian Hellenic (and not universal) system of government. In one of his speeches, he said "We are Hellenes by race and culture". He is at the forefront of historical studies exploring the connections between Byzantine and Modern Greek identity.

Laonikos Chalkokondyles (c. 1430 - 1470)

Chalkokondyles was an Athenian native, from a prominent old family of the city. He was a historian who witnessed the last years of the Byzantine and the early years of the Ottoman Empire. He was sometimes employed by the Byzantine emperors as a messenger to the Sultan Mehmed II, not without drama. Chalkokondyles wrote in detail about 150 years prior to his lifetime. He described the fall of the Byzantine Empire, he offered a profile of the Ottoman Turks, and he wrote about their conquest of the Venetians and Matthias the King of Hungary. He also explored the civilisations of England, France and Germany. I didn't know about him until I read a great Romanian biography of Vlad Tepes the Impaler (you know, the inspiration of Count Dracula). Chalkokondyles's input is extensive and invaluable for this book; he wrote about Vlad's ancestors and the fights of the Wallachian princes with the Ottomans. His style of writing was mostly clear and simple, styled after Thucydides. He called the Byzantines “Hellenes” and did not use the term "Rhomaioi" (Romans in Greek) for them.

#byzantine empire#eastern roman empire#history#medieval history#middle ages#byzantine history#greek history#greeks#greek people#attichoney4u#ask#long post#tw long#long text#tw long text#tw long post

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isabella of Villehardouin (1260/1263 – 23 January 1312) was reigning Princess of Achaea from 1289 to 1307. She was the elder daughter of Prince William II of Achaea and of his third wife, Anna Komnene Doukaina, the second daughter of Michael II Komnenos Doukas, the despot of Epiros.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

@just-late-roman-republic-things

I think for the women section in Byzantine, you can add Aelia Eudoxia, the wife of Arcadius, Aelia Pulcheria (problematic though, not sure if you want to include her) Aelia Eudocia, the wife of Theodosius II and Galla Placidia.

Anna Komnene who is the author of the Alexiad, a biographical work that accounts Alexios I Komnenos' reign, her father.

Her mother Irene Doukaina.

Empress Theodora, wife of Justinian the Great (I) (for obvious reasons and a famous one, not sure if you include her in your list.)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saints&Reading: Friday, March 29, 2024

march 16_ march 29

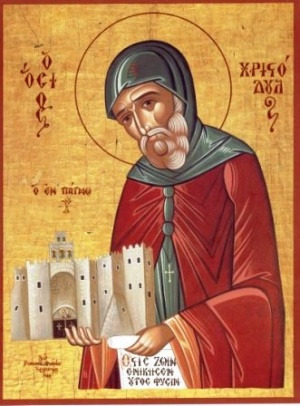

Venerable Christodulus, wonderworker of Patmos (1093)

VENERABLE CHRISTODULUS, WONDERWORKER OF PATMOS, MONK (1093)

Our Venerable Father Christódoulos 1) was born near Nicaea of Bithynia circa 1020. His parents' names were Theodore and Anna, and their son received the name John in Holy Baptism. He was renowned as an ascetic and a physician throughout the Byzantine Empire.

In 1043 he was tonsured on Mount Olympus, where, under the guidance of the Elders, he received a broad education. After the death of his Spiritual Father, he made a pilgrimage to the holy places in 1045. He visited Rome and Palestine, and he lived in Asia Minor, and on some Greek islands, where he founded several monasteries.

After the Saracen invasion of Palestine, Father Christódoulos left the Holy Land and in 1070 settled on Mount Latmos, in the stavropegial Monastery of the Theotokos in northwestern Karia. Soon he was chosen as the Superior of that monastery. In 1076, Patriarch Cosmas I of Constantinople installed Father Christódoulos as Archimandrite over all the Latmian monasteries. From 1076–1079, he labored to build and fortify monasteries.

In 1079 the Latmian monasteries were destroyed by the Seljuk Turks. The Saint took refuge with his small community in the city of Strovilos on the Aegean coast, where the hermit Arsenios placed him in charge of his monastery. Father Christódoulos soon moved to the nearby island of Kos, the least affected by Muslim incursions. There Arsenios had several estates, and on Mount Pelion, at the latter's suggestion, Christódoulos founded the Kastrian Monastery of the Most Holy Theotokos in 1080.

In 1087, he founded a monastery on the neighboring island of Leros. In addition, during his stay on the island of Kos, Saint Christódoulos organized an expedition to Mount Latmos in order to rescue the books from the monastic community which he had abandoned. These books were sent to the library of the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople for safekeeping.

Seeking greater solitude and austerity, Saint Christódoulos turned his attention to the island of Patmos. He was so struck by the ascetic spirit of these places that he decided to establish a monastery on that island. In 1089, he submitted his first application to Emperor Alexios I Komnenos for a new monastic community on the island of Patmos, in place of the land on the island Kos and on the shores of Karia.

According to a Chrysobull issued in 1088, the Emperor gave the island of Patmos to Father Christódoulos as an eternal, inalienable property, exempting it from all taxes. It forbade government officials to act on the island. In fact, the island was withdrawn from the jurisdiction of the state's administration, and all judicial and administrative power on this island was concentrated in the hands of the Igoumen of the Monastery.

The Venerable one established a monastery on a mountain near the cave, where, according to Tradition, the Holy Apostle John the Theologian received a divine revelation and wrote his prophetic book in the years 68-69. The monastery was built on a rocky ledge, almost in the center of the island, and during the first three years, it had acquired the appearance of a fortress.

However, in the last years of his life, because of the raids of pirates, the Saint was forced to flee Patmos. He and his disciples went to the island of Euboea, where he reposed on March 16,1093. Shortly before his death, he gave his disciples instructions to bury him on the island of Patmos in the Monastery he founded. His disciples took his holy and incorrupt relics and transferred them to his own Monastery, where they remain for the sanctification of those who venerate them with faith.

Saint Christódoulos is also commemorated on October 21 (the transfer of his holy relics).

1 His name means "the servant of Christ."

Source: Orthodox Church in America_OCA

ISAIAH 7:1-15

1 Now it came to pass in the days of Ahaz the son of Jotham, the son of Uzziah, king of Judah, that Rezin king of Syria and Pekah the son of Remaliah, king of Israel, went up to Jerusalem to make war against it, but could not prevail against it. 2 And it was told to the house of David, saying, “Syria’s forces are deployed in Ephraim.” So his heart and the heart of his people were moved as the trees of the woods are moved with the wind. 3 Then the Lord said to Isaiah, “Go out now to meet Ahaz, you and Shear-Jashub your son, at the end of the aqueduct from the upper pool, on the highway to the Fuller’s Field, 4 “and say to him: ‘Take heed, and be quiet; do not fear or be fainthearted for these two stubs of smoking firebrands, for the fierce anger of Rezin and Syria, and the son of Remaliah. 5 Because Syria, Ephraim, and the son of Remaliah have plotted evil against you, saying, 6 “Let us go up against Judah and trouble it, and let us make a gap in its wall for ourselves, and set a king over them, the son of Tabel”— 7 ‘thus says the Lord God: “It shall not stand, Nor shall it come to pass. 8 For the head of Syria is Damascus, And the head of Damascus is Rezin. Ephraim will be broken within sixty-five years, so it will not be a people. 9 The head of Ephraim is Samaria, And the head of Samaria is Remaliah’s son. If you will not believe, Surely you shall not be established.” 10 Moreover, the Lord spoke again to Ahaz, saying, 11 “Ask a sign for yourself from the Lord your God; ask it either in the depth or in the height above.” 12 But Ahaz said, “I will not ask, nor will I test the Lord!” 13 Then he said, “Hear now, O house of David! Is it small for you to weary men, but will you weary my God also? 14 “Therefore the Lord Himself will give you a sign: Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a Son, and shall call His name Immanuel. 15 “Curds and honey He shall eat, that He may know to refuse the evil and choose the good.

GENESIS 5:32-6:8

32 And Noah was five hundred years old, and Noah begot Shem, Ham, and Japheth.

1 Now it came to pass, when men began to multiply on the face of the earth, and daughters were born to them, 2 that the sons of God saw the daughters of men, that they were beautiful; and they took wives for themselves of all whom they chose. 3 And the Lord said, “My Spirit shall not strive with man forever, for he is indeed flesh; yet his days shall be one hundred and twenty years.” 4 There were giants on the earth in those days, and also afterward, when the sons of God came in to the daughters of men and they bore children to them. Those were the mighty men who were of old, men of renown. 5 Then the Lord saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every intent of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually. 6 And the Lord was sorry that He had made man on the earth, and He was grieved in His heart. 7 So the Lord said, “I will destroy man whom I have created from the face of the earth, both man and beast, creeping thing and birds of the air, for I am sorry that I have made them.” 8 But Noah found grace in the eyes of the Lord.

#orthodoxy#orthodoxchristianity#easternorthodoxchurch#originofchristianity#spirituality#holyscriptures#bible#wisdom#saints

1 note

·

View note

Text

We begin construction of a city in our empty holding in the County of Leon, Valencia de Campos. The city holding cost us 400 gold and would be ready in 5 years.

King Fernando initiates a Learn Language scheme on Shaykhah Hawa' of Alarcos who is Amazonian and an Andalusian, to learn her language of Arabic.

A slightly more powerful Masterwork Castilian Regalia has been forged by Anna Komnenos-Antioch, which King Fernando gratefully equips.

In peacetime, King Fernando holds court and receives petitions from 2 of his relatives - the first one from his uncle Kussil ibn Yahya Dhunnunid who wants King Fernando to aid him in conquering the Shiekhdom of Alarcos, to which King Fernando replies that he cannot help but encourages Kussil to enjoy his hospitality. The second is from King Fernando's nephew Duke Alfonso, who wants guaranteed council rights, to which King Fernando agrees to but in exchange for higher taxes.

King Fernando goes on a hunt to reduce his stress and comes across an extremely large bear that took half a day to wound and fell. We add the Skull of the Cursed Bear of Avila to our Small Wall Ornament collection.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

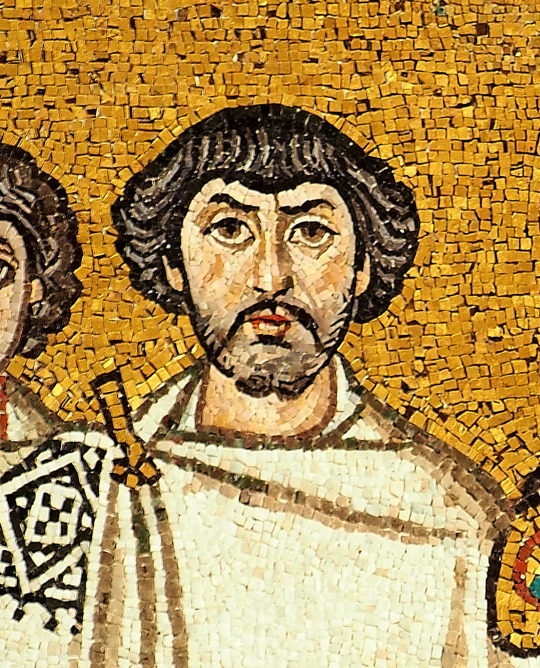

Mosaic art in the Byzantine Empire

12th century mosaic of Alexios I Komnenos, the father of the Anna Komnene, the author of the Alexiad. The mosaic of him and his son, John II, can be found in the iconic Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.

It is undeniable that material culture -- like many other cultural manifestations -- can inform us about history. Byzantine mosaics are one of the most intricate and vibrant art forms that originated in the Byzantine Empire, which existed from the 4th to the 15th century. These mosaics played a significant role in Byzantine art and are renowned for their rich symbolism, religious themes, and meticulous craftsmanship.

During the Byzantine empire, three dimensional sculptures, often used to depict pagan deities, were replaced by its two dimensional counterpart: mosaics. This was a shift from the Classical period, where mosaics were used to adorn floors -- during the Byzantine era, mosaics were crafted on walls and ceilings, and the flat lightweight stones provided the advantage in doing so. Portable mosaics were considered a luxury, and most portable Byzantine mosaics were produced in Constantinople. It was also during the Byzantine period that further artistic techniques were developed, where more materials -- like gold leaves and precious stones -- were used as tesserae and were strategically placed to reflect light.

External sources:

0 notes

Text

Time for silly guesses where I'll be 100% wrong. From left to right.

Morgause or Nimueh or whoever's the Lady of the Lake is lol/ Helena, Constantine's mom because it'll be hilarious.

Justinian/ Alexios I Komnenos/ Basil the Bulgar Slayer/I'm just putting random Byzantine emperors for kicks here.

Carlo Magno

A Song of likely being out of NPC hell

Eleanor of Aquitane/ Theodora/ Anna Komnena/ Olga of Kiev/Teresa of Avila/ I don't know what I'm doing

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...As well as considerable numbers of women among the poor pilgrims following the crusaders, there were always some working women following medieval armies, some doing laundry and kitchen work or nursing the wounded and others providing sexual services. When fighting broke out, women contributed by carrying drinking water and comforting the wounded. A number of aristocratic ladies in addition to Eleanor followed their crusader husbands, and they brought along servant girls and ladies in waiting, swelling the total number of women.

Eleanor’s own personal entourage must have been quite large but the legend that she recruited a band of armed and mounted “Amazons” to ride with her alongside the crusading knights can be set aside. This improbable story apparently originated with a Greek chronicler’s description of the crusaders’ entry into Constantinople, written at least a generation after the event. The legend was taken up enthusiastically by nineteenth-century writers and is repeated in widely read twentieth-century books on Eleanor.

The vast army made its way to Metz after a four-or five-day march from Paris and then marched on to Worms, where it crossed the Rhine. A traveler on horseback could average thirty-five miles a day, but Louis’s host was slowed by many persons on foot, slow-moving packhorses, and cumbersome two- and four-horse baggage carts and wagons clogging the roads. At Regensburg in Germany, baggage was loaded on barges to be sent down the Danube as far as Bulgaria, relieving the army of the carts that had “afforded more hope than usefulness” and raised much complaint from military men for holding up their progress on land.

A great deal of the supplies belonged to Eleanor, and her bulky baggage would cause criticism later. Even with her more than ample supplies, she could not have found travel conditions comfortable. A medieval road “hardly existed as a physical object,” being little more than a track connecting towns and villages, often containing impassable mudholes in wet weather. If Eleanor chose not to ride a horse, she could have had herself carried between two horses on a litter, as was common for noble ladies. She and other aristocratic ladies may have ridden part of the way in “chariots,” uncomfortable but highly decorated carts. Wheeled vehicles were not equipped with springs, and nobles usually disdained carts for their rough ride and also for their demeaning associations with peasants and laborers.

…On 4 October 1147, after a five-month journey, Louis and Eleanor arrived before the walls of Constantinople with the crusading army and its accompanying pilgrims. From the first sight of the massive Theodosian walls protecting the western approach, the great city made a powerful impression on Eleanor and her companions, even though at the time of the Second Crusade it was past its prime, the capital of a shrunken and weakened empire. Its great churches and palaces constructed under Constantine and Justinian were still standing and in daily use, unlike in Rome, where the Roman imperial monuments had fallen into ruin long ago.

The “Great” or “Sacred Palace” overlooking the sea had periodically been enlarged and renovated and had grown into a city within a city. Connected to the palace complex were the nearby Hippodrome and the church of Hagia Sophia, illustrating the links between the emperor, his people, and the Church. Since the eleventh century, the imperial family had abandoned the Great Palace, favoring the Blachernae Palace built next to the city wall at the western landward edge of the city near the Golden Horn.

It was to Blachernae that Louis was led for his first meeting with the emperor Manuel Komnenos. Odo of Deuil describes the palace: “Its exterior is of almost matchless beauty, but its interior surpasses anything that I can say about it. Throughout it is decorated elaborately with gold and a great variety of colors, and the floor is marble, paved with cunning workmanship; and I do not know whether the exquisite art or the exceedingly valuable stuffs endows it with the more beauty or value.”

At the gates of the city, Louis and his queen were met by a delegation from the city’s nobles and prominent citizens who welcomed them and invited them to meet their emperor. Odo of Deuil, observing the meeting, left a description: “When we approached the city, lo, all its nobles and wealthy men, clerics as well as lay people, trooped out to meet the king and received him with due honor, humbly asking him to appear before the emperor and to fulfill the emperor’s desire to see and talk with him.” Louis, “taking pity on the emperor’s fear,” agreed, and his first encounter with the Eastern emperor at the Blachernae Palace was cordial.

Byzantine court etiquette with its obsequious obeisance to the emperor scandalized the French, but a concession was made to Louis, allowing him to sit in the emperor’s presence. The chronicler notes, “The two sovereigns were almost identical in age and stature, unlike only in dress and manners.” Eleanor is not mentioned in the account, but it is probable that she was anxious to accompany Louis on his first meeting with the Byzantine ruler to see him and his court for herself.

Manuel Komnenos made available to the French king and queen the Philopatium, a hunting lodge outside the city wall near the Blachernae Palace, and the army and the many servants and pilgrims following it camped nearby. The French crusading army spent about three weeks at Constantinople, crossing over to the Asian side of the Bosporus on 26 October. The emperor took Louis on sightseeing tours, showing him the many churches and their collections of holy relics, and after their tours he invited Louis to dine with him. The banquets at the emperor’s palace “afforded pleasure to ear, mouth, and eye with pomp as marvelous, viands as delicate, and pastimes as pleasant as the guests were illustrious.”

Meanwhile Eleanor and the empress were exchanging letters and becoming acquainted. The wife of Manuel Komnenos was German, the sister-in-law of the emperor Conrad, Bertha of Sulzbach. She had received a new name, Irene, after her marriage and conversion to the Eastern Orthodox religion in 1146. In theory, respectable Byzantine ladies were expected to be seldom seen and never heard in public. The empress’s quarters in the palace were under her sole control, guarded by eunuchs, and men were never supposed to enter—not even the emperor, unless with her permission.

Yet in the twelfth century, Byzantine women, except for unmarried girls, were no longer so secluded as in earlier centuries, and the empress and her ladies attended receptions and banquets. Empress Irene and her guest Eleanor likely joined their husbands in the evening to dine with them in the emperor’s quarters. Louis, “a simple man who made a duty of simplicity,” soon found the excessive ceremonial and the extravagant titles of the many Byzantine court officials exasperating. His growing distaste for Constantinople was shared by his men as friction arose with the city’s money changers and merchants, whom the French suspected of price-gouging and of disdaining them.

Eleanor’s impression of the Byzantine capital and the imperial court, however, was not likely to have been as negative as that of her husband and her countrymen. Perhaps Byzantium evoked memories of the sensuality and luxury of life at the Poitevin court, and she savored the contrast between the gorgeous spectacle of the imperial court’s ceremonies and the dull and drab Capetian royal court that she had left behind. Constantinople’s glories opened Eleanor’s eyes to “vast, lofty, undreamed-of possibilities for majesty.”

…In the half-century since the First Crusade, bitterness between crusaders and Eastern Christians had accumulated, building “a wall of incomprehension.” Crusading westerners visiting Constantinople felt inferior to the Byzantines, and they compensated by condemning the Greeks as over-civilized, too soft, effeminate, and degenerate for their tastes. Furthermore, western Christians condemned Eastern Orthodox Christians as heretics, and the chronicler Odo of Deuil reveals the ferocity of their hatred of Orthodox doctrinal errors.

He writes, “Because of this they were judged not to be Christians, and the Franks considered killing them a matter of no importance and hence could with the more difficulty be restrained from pillage and plundering.” Greeks regarded westerners as coarse and crude barbarians, as shown by Anna Komnena’s account of the conduct of those passing through Constantinople on the First Crusade.

She wrote, “Now the Frankish counts are naturally shameless and violent, naturally greedy of money too, and immoderate in everything they wish, and possess a flow of language greater than any other human race.” The behavior of the armies of the Second Crusade did nothing to change attitudes at the imperial court or among the people. Complaints about merchants and money changers’ cheating roused the crusaders to violence: they took with force what they could not buy, and they spoke openly of conquering Constantinople.”

- Ralph V. Turner, “Adventures and Misadventures on the Second Crusade, 1145–1149.” in Eleanor of Aquitaine: Queen of France, Queen of England

#eleanor of aquitaine#eleanor of aquitaine: queen of france queen of england#high middle ages#crusades#history#byzantine#medieval#french

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 is Zoe

2 is Anna Komnene

3 is Andronikos

4 I'm not sure of.

5 is Zoe

6 is something from the Crusades?

7 I have no clue about

8 Manuel Komnenos and Agnes of France

9 is Isaac II Angelos

10 is Niketas Koniates (LOL)

Byzantine Empire, 11th-13th Centuries + The Onion Headlines

91 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you explain the monarchy of the Byzantine Empire? Was it elective or hereditary?

The problem with the Byzantine Empire is that there was no codified form of succession, and plenty of emperors came to power in all sorts of fun ways.

In peacetime, an Emperor might pick a favored relative and confer imperial titles upon them, such as Kaisar, or even crowning them as a co-emperor so that the purple would automatically revert to them. It wasn’t uncommon, for example, for an emperor to crown their young son as co-emperor, despite the fact that said son would be doing no emperor-ing of any kind. Those children who were born when the Emperor was ruling, in the Purple Chamber, were given the title “Porphyrogénnētos” literally born in the purple, and were seen as having a greater right to rulership. A regent might also be a co-emperor to an infant ruler, so say for example Emperor ChronicallyUnlucky names his infant son QuiteUnfortunate as co-emperor, then slips on a banana peel and falls out a window because he refused to listen to time-traveling OSHA regulations. QuiteUnfortunate becomes the new emperor, and his regent, Uncle Nepoticide, is named as regent. Nepoticide would probably immediately have the baby smothered in his crib, chalk it up as a case of crib death after bribing the physician, then name his son You-Know-Where-This-Is-Going as co-emperor.

But, there were also electoral procedures High-ranking officials sat on the council and they could vote when the succession was in doubt, this was the case for Emperor Anastaisus and how Justin the swineherd became Justin I (though it was really more like Justin the palace guard commander became Justin I, that’s not as catchy though), after essentially taking bribes used to secure his support since he controlled the palace to bribe the council to vote for him. Typically though, the council knew who the Emperor intended as heir and usually confirmed the Emperor’s intent since typically naming them to the position of co-Emperor was a move done with the consent of the council.

Not confused enough? Good, because those were considered ideal circumstances. In crises, or when an Emperor badly botched a military campaign or handling droughts and plagues or something or other, the troops might revolt, proclaim their strategos as the new Emperor and attempt to depose the Emperor, either by capturing the royal person or seizing the palace. Several different troops could do this, as could different noble factions, most of whom had their own private armies as well, which could mean a bunch of barracks emperors duking it out for who gets control. You might know this as the Crisis of the Third Century in the Roman Empire, but this happened in the Byzantine Empire too. This is also why Belisarius, when the Goths offered to make him Emperor of the West, was not seen as something strange or bizarre, because such things had happened before in Roman history. After all, one of the principal powers of the Roman Emperor was imperium, the right of military command. The Emperor was the imperator, and in the Byzantine Empire, that title was maintained as the autokrator.

And of course, we cannot rule out good old-fashioned intrigue, such as the absolutely splendid Anna Dalassene using every trick in the trade to get Alexios out of the city so he could become the ruler and founder of the Komnenos ruling dynasty.

This is abbreviated by the way, there was so much complex and bizarre stuff rolling around regarding Byzantine and Roman succession that historians have made it their entire careers to explain it. There are books written about how complex the politics of these empires were, even some that talk about early republican methods (though we wouldn’t mistake them for anything resembling republican democracy today) that came into effect. So don’t worry about it being as clear as mud, that’s just how it is.

Thanks for the question, Anon.

SomethingLikeALawyer, Hand of the King

70 notes

·

View notes

Note

How was life during the Byzantine empire and how different was with the rest of Medieval Europe?

I am afraid this could be the content of a proper book as it is very generic. I was trying to find something that could help me make a short enough post and I stumbled over this gem

My new gender is "effeminate person that speaks to statues" from now on although "Small Greek" (Graecula?) might be just as accurate

Yeah anyway the Byzantine Empire was the most advanced European and West Asian state of the Middle Ages from the 4th to the 11-12th centuries, as after that its collapse and the simultaneous fast rise of the West begin.

The Byzantine Empire had the largest and very diverse and rich cities, so beautiful that they attracted travellers from all over the known world just to see them (medieval tourists in short 😝). Constantinople more than any other, which chroniclers of the time sometimes described as “glowing with gold”. It was the center of the world's trade at its peak, it traded products between the East and the West.

It had universities and almost all people were getting at least some level of education, even if basic, including girls. It likely had the lowest percentage of women's illiteracy. Of course there was serious inequality by today’s standards but Byzantium was still one of the best places to live as a woman in the middle ages. Women had properties, ran their own businesses, could ask for divorce (in extreme circumstances) and could remarry but they were not obligated to. Women also participated in all festivities alongside men. There are also a few instances of women being influential and strong minded creators, like authors and poets (ie the aforementioned Anna Komnene, and not Komnenos as it says above, surnames here are gendered guys, stop turning all Greek women into dudes)

Byzantium preserved and studied extensively Classic philosophy, literature and science at a time these were still unknown to the west.

While Byzantium is perceived as an extreme Theocracy, in reality the Patriarch (the Orthodox equivalent of the Pope) was subordinate to the Emperor (unlike the Pope and the western kings) and therefore the emperor could oppose to the patriarch if his decisions were getting too much against the secular state's benefits. While the emperor was viewed as a saint on earth, this view was rather superficial and full of pretense. The commonwealth could get very easily restless and agitated when the emperor didn't meet their needs - this is why peasants and the army would often collaborate and overturn an emperor. Therefore, in the Byzantine Empire anyone could claim the throne no matter how humble his background was as long as he was skilled, intelligent, brave, popular and ruthless (or at least determined) enough. In general, even though there were social hierarchies, it was a place where you could rise in power, wealth, education and status despite your origins if you tried a lot or had a fair amount of cunning. Oh and the Byzantine Empire was the only medieval state to have been ruled by four women (a few of them ruthless indeed) without a man (or with a man being just a consort, I believe). But also, all empresses were expected to temporarily rule if their emperor husband was at war or sick, therefore they were always involved in the empire's affairs and their opinion mattered hugely both with the emperor and the court. Some empresses had very humble backgrounds as well and, you know, that’s kinda a big deal when it comes to medieval women. Even women could rise in power despite their background.

The Byzantine Empire liked festivities, showing off, luxuries, having fun - because, again, the commonwealth had to be satisfied. Peasants didn’t eat meat often, however there was a considerable diversity in the cuisine and also feasts where meat was offered for free to all.

There were also some technological feats (like some early robotlike devices), weapon innovations and medicine advancements like some pretty elaborate surgeries (including the first separation of conjoined twins - it would be attempted again 700 years later). The hospital as we know it today (trying to cure the patients) is a Byzantine invention as up to that point a hospital was just a place to accomodate dying people. The Byzantines took better care of their hygiene (there are records of Western Europeans being confused at how often Byzantine princesses wanted to take a bath).

About the worse stuff, the Byzantine Empire might have been one of the most invaded or threatened states in history, even by medieval standards. A war was experienced by every second generation on average! Invaders attacked from all sides. However, the cities had very strong walls, the Byzantine army was pretty strong (and hired good warriors from all Europe and Anatolia) and Byzantine diplomacy was also pretty advanced, often offering taxes and tolls to avoid conflicts. Such measures could rapidly impoverish the empire and the emperor had to impose huge taxes and then as said above the peasants would riot and the emperor would fall and the next one would either fight off the aspiring invaders or hide the financial issues until the next riot or happened to be a very competent ruler that led the empire to a new era of development and financial prosperity. This happened so many times that it made the empire a hilarious rollercoaster in terms of the economy. Nevertheless, it always kept the façade of luxury even at its worst. With that way or another (even if it might seem at times a not very proud way), the empire lasted and flourished longer than any other Medieval state until its pretty gruesome downfall.

Everything I mentioned above was better than the respective conditions in Western Europe in the Middle Ages. However, excuse any potential inaccuracies because it’s hard to shorten such a big topic and it might have some generalisations. I do believe what I wrote is pretty accurate though.

64 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Irene Doukaina or Ducaena (c. 1066 – 19 February 1138) was a Byzantine empress by marriage to the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos. She was the mother of Emperor John II Komnenos and the historian Anna Komnene.

4 notes

·

View notes